Obligatory Peter Drucker quote, “you can’t manage what you can’t measure.”

Requests for Proposals in legal : a seemingly simple solution, but can get complicated. (Um first, what is an RFP?) RFPs should save you money and time (see why they’re so great in general), but the results of an RFP can sometimes be poorly communicated internally. Why? Lack of appropriate savings measurements.

One large part of reducing legal fees over time is to measure savings after running an RFP for legal services and then to communicate those savings to drive use of more RFPs . To ensure that you’re actually communicating savings effectively after you run RFPs to engage outside legal counsel, we’ve written the following guide.

Why is it important to measure savings after running a Legal RFP?

Measuring savings after running an RFP is critical to determining the success of the program in driving the right financial outcomes and decisions. While there may be some instances where choosing the most expensive firm is the right decision, this should be challenged if it’s happening all the time. By measuring savings, corporate leadership can ensure that it holds the team members accountable for being good stewards for their shareholders.

What are the different cost-saving methods for Legal RFPs?

There are a number of methods to calculate savings after running an RFP, and some work better than others given particular goals. Let’s get into it, shall we?

Legal RFP Savings Calculation Methods:

1. Highest Starting Price vs. Final Accepted Price from Law Firms

How it works

This method takes the most expensive proposal and compares it with the proposal's final accepted price, after negotiations. This method is most generous to the person running the RFP.

The Pros

This approach is positive in that it highlights the dangers of “single sourcing.” Single sourcing refers to the practice (that of which is not uncommon in the legal industry) of reaching out to a single, preferred firm or supplier and hiring them without obtaining quotes or bids from other firms. Identifying the highest-priced firm in a savings calculation demonstrates the amount of pay avoided in a single sourcing scenario.

The Cons

This method may lead to very high savings numbers, which, in some instances, can exceed the amount paid for the service. Because these high savings numbers lead to high savings percentages - savings may not be believable to stakeholders.

While this method is valid, it does not deliver if the goal of the savings calculation is to encourage more RFPs via the continued confidence of stakeholders. A more conservative, believable metric presented by leadership may drive desired behaviors from stakeholders.

Also, the high bidder in this equation could be an extreme outlier. Thus it is not always appropriate to use this bidder as the baseline for savings - especially where all the other bidders were closer together in price.

Example 1 of how to measure savings after running an RFP for legal

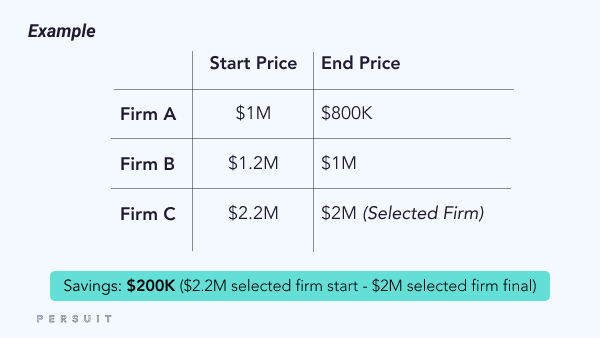

2. Selected Law Firm’s Starting Price vs. Selected Firm’s Final Price

How it works

This approach compares the selected firm’s initial starting price to begin the RFP process to the selected firm’s final agreed price. This approach highlights how much a firm has reduced its price based on negotiations or because of a reverse auction.

The Pros

This approach partially solves the issue present in the first example in that it ignores any large outlier bids. It also highlights changes that couldn’t have occurred without the competitive process. This demonstrates clear price movement and gives credit for good negotiation tactics.

The Cons

While this is a good way to highlight a selected firm’s price movement, the approach neglects to consider the other bids received. This is problematic because a client could select the highest priced firm and claim to have saved money because that firm reduced its price.

If you end up paying more than $1M above the market average, then it seems counterintuitive to claim savings just because you negotiated down the selected firm.

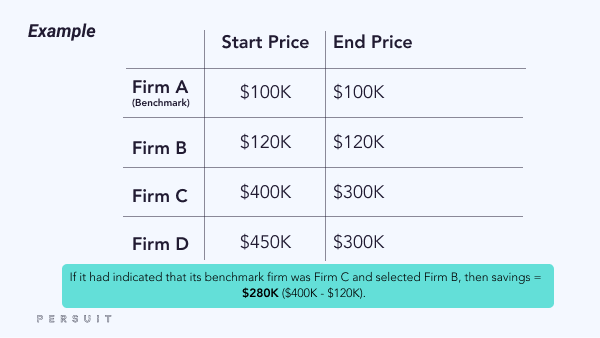

3. Benchmark Law Firm’s Starting Proposal vs. Selected Law Firm’s Final Price

How it works

A benchmark firm is the firm that the client indicates that it would have chosen in a single sourcing scenario. In other words, it is the presumptive choice going into the RFP ( possibly because the firm did the same work for the client in the past, or some other reason). This method compares the benchmark firm’s starting price to the selected firm’s final price.

The Pros

This approach gets high marks for attempting to capture the value of the RFP process in changing the mind of the decision maker to choose a lower cost firm. This is helpful in demonstrating the value of the tendering process.

The Cons

The downside to this approach is that it assumes that there is a benchmark firm: sometimes there is no presumptive choice before receiving bids. If this is the case, a benchmark firm must be identified, which may present a challenge. Another problem with this approach appears when the client selects a non-benchmark firm that is higher than the benchmark firm but still markedly lower than the market average. It seems unfair to not receive credit for savings in such a scenario.

Example 3 of how to measure savings after running an RFP for legal

Note:

- If the selected firm is Firm B – then savings are $0, since its price exceeds the final price of the benchmark firm (Firm A).

- If the client selects the Benchmark firm (Firm A), savings also are $0, since it did not drop its price.

- If it had indicated that its benchmark firm was Firm C and selected Firm B, then savings would equal $280K ($400K - $120K).

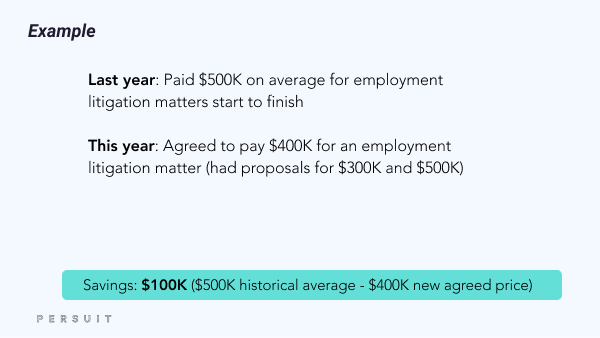

4. Historical Price vs. New Price for Same Service from Law Firm

How it works

“Savings” usually implies paying less for something than you used to pay or could have paid. This method focuses on the former, “used to pay” qualification. By paying less in Year 2 for the same service client paid for in Year 1, the client can claim a “cost reduction” savings.

The Pros

The benefit of this approach is that it focuses on the actual dollars spent by the client in the past as the baseline for the savings, rather than dollars that “would have” spent. This approach feels more concrete in terms of actual bottom-line savings, rather than an approach that looks at pricing in proposals that never were paid to determine savings.

The Cons

While this approach works great for simple ‘widgets,’ (e.g. “I paid $10/bottle last year, paid $8/bottle this year, so saved $2”) the approach poses more difficulty in professional services categories. This is because the scope of work for a professional service engagement (like a legal service) is rarely the same as that of which was provided in the prior year. Therefore, finding a baseline example upon which to compare this year’s price to last year’s price could be difficult, or impossible.

5. Lowest Law Firm’s Starting Price vs. Lowest Law Firm’s Final Price

How it works

The firm that starts the RFP with the lowest bid is the baseline. If the client selects a firm whose bid ends up lower than the initial lowest bid (could be the same firm if the lowest firm reduces its price), then the delta is the savings amount.

The Pros

This approach is very conservative in that it highlights how much the RFP lowered the floor of the market in terms of price. Fluctuations in the highest bidder’s price won’t skew the savings results. For clients that have a strict policy of choosing the lowest bidder, this savings mechanism works well.

The Cons

Focusing on the lowest bidder is too conservative of an approach for most clients. This also ignores which firm was selected. While this approach could be reasonable in direct materials categories, the professional services industry differs in that the lowest bidder is not as frequently selected, and therefore ignores any reduction in historical price or any delta between the selected firm and the other bidders.

6. Average Starting Price v. Final Accepted Price from Law Firm

How it works

When multiple firms submit bids, this formula compares the average starting price of those bids with the final agreed price of the winning bidder.

The Pros

This approach focuses on the market average as the baseline for savings, which is a great way to introduce an objective marker of what most companies would pay for a given service. Comparing the market rate/fee for a service with the rate/fee paid by your company is a great way to capture the value that the competitive process delivered. This works well for services that have scopes that vary widely from project to project: such ambiguous projects usually don’t have a historical comparison value available -- which is most often the case in the legal services category.

The Cons

The only downside here is that a focus on the average starting price could be skewed upward or downward by outlier bids.

Conclusion

What is the best savings calculation method for legal services?

The average starting price v. the final accepted price is the best method for legal services. Legal services contain nuances that present too many challenges when looking at the historical price as a baseline for savings. Further, this approach is more conservative (therefore, in some cases, better) and avoids cherry-picking the price of the highest bidder for comparison (which may often be an outlier). The runner-up method here would probably be - selected firm’s starting price vs. selected firm’s final price. However, focusing solely on the change in price of the selected firm neglects the fact that the selected firm could be a major outlier and so without a look at the other firms participating seems too narrow of a perspective to accurately calculate savings.

How much do corporate legal departments save on average using this methodology?

Across hundreds of RFPs and hundreds of millions of dollars in spend, PERSUIT has analyzed the average savings achieved by corporations that run RFPs for outside counsel legal services. The average savings (using the preferred method of Starting Average v. Final Accepted) is 20% for RFPs without auction and 37% for RFPs that also included a reverse auction. This means that auctions drive an incremental 17% in reduction of the final selected firm. This greatly underscores the need for legal departments to give firms transparency and to allow counsel a chance to submit additional bids to be more competitive.